History

Five Generations of Builders

In 1886, three brothers and one sister joined the first William Steele in what was then known as William Steele and Son, Carpenters and Builders. As Philadelphia’s most prominent team of designers and builders, the company established a reputation for excellence, inventiveness and imagination. The company would go on to build Philadelphia’s first skyscraper as well as numerous hospitals, medical suites, theatres, classrooms and commercial buildings, including the former Shibe Park, (later known as Connie Mack Stadium).

Today’s William Steele & Sons is an insured and bonded company that continues to provide a suite of healthcare building services from design through completion. To learn more about our solid, affordable solutions to health and wellness construction or to speak to us about a different industry facility development, renovation, maintenance or expansion project, please call us today or email us at sclemmer@wmsteeleandsons.com.

Through the Years

From the closing decade of the 19th century until the Great Depression of the 1930s, William Steele, and his sons and grandsons created Philadelphia’s most prominent company of designers and builders. It was an era of new ideas, inventions and innovations. As Joseph became the driving force, introducing new ideas and construction techniques, the company’s focus changed from house building into large-scale construction.

First Skyscraper

c. 1895-1897

Using I-beams perfected by Andrew Carnegie, the Steeles erected Philadelphia’s first skyscraper, the Witherspoon Building (1895-1897) two blocks south of City Hall.

With a steel framework, the Witherspoon Building at Walnut and Juniper Streets housed the Steeles on the 9th floor until moving to their new home at 16th & Arch Streets. Alexander Milne Calder designed ornate sculptures for both buildings, including the statue of William Penn atop City Hall.

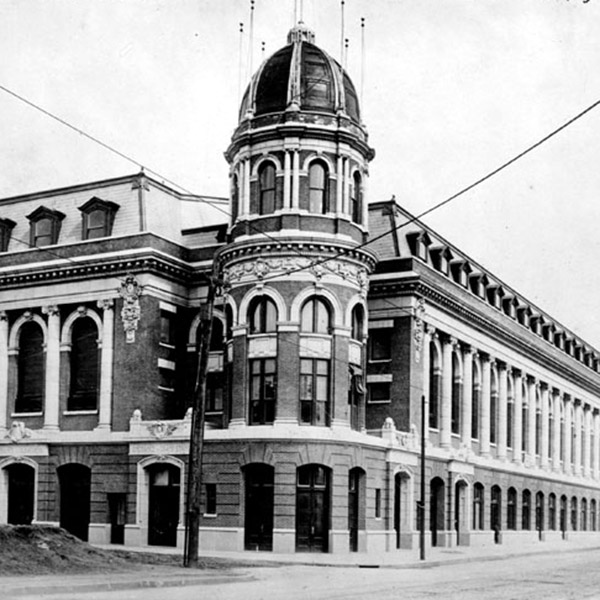

Shibe Park (later Connie Mack Stadium)

c. 1909

Ironically, the project for which the Steeles became famous — Shibe Park, later called Connie Mack Stadium — is gone. In its stead, at 21st and Lehigh Ave., is a church and shopping center.

Only superlatives suited the new ballpark. It was the nation’s largest, most luxurious and at more than $500,000, the most costly. It was also the first erected with steel and reinforced concrete. Unfortunately, the company’s founder, William Steele, died in 1908, the year before “play ball” was first heard. Popular with fans for a half-century, Shibe Park fell victim to the automobile. The lack of parking brought its demise in 1970, when home plate was airlifted by helicopter to the new Veterans Stadium, also now gone.

Broad Street Subway c. 1928

A Steele innovation in reinforced concreate earned a company related to the Steeles the concrete contract for the Broad Street subway.

Guided by an engineer brought from Sweden, the company experimented with reinforcing bars and rods — finally perfecting the ideal material for large structures, reinforced concrete. It was cheaper, faster to use, fireproof and nearly indestructible. Maintaining quality was a problem in concrete batch-mixed at the site. The solution: central mixed concrete delivered by trucks. But another problem arose. During delivery, gravel tended to settle and water rose to the top. The solution was to build a truck with a revolving barrel lined with blades. Transit mix concrete was born.

Market Street National Bank c.1931

Elaborate art deco terracotta adorns the Market Street National Bank at Market and Thirteenth Streets across from the northeast corner of City Hall in Philadelphia.

This building is now a residence hotel. For economy, the company used standardized modules but added distinctive facades. Today, the building is still a representative example of the Art Deco style of the 1920s and 1930s.

Reading Railroad c. 1931

The Steeles erected the largest commercial building of its time — 401 North Broad Street — over the railroad tracks.

The Reading Railroad wanted a million square feet of floor space, a freight station and truck concourse with loading docks — all in one building. No problem. It became the city’s second structure to use “air rights.” The first was across the street. The Philadelphia Inquirer newspaper unloaded boxcars of newsprint directly into the pressroom.